New observations on biology and ecology of two weevil species, Bagous lutulosus (Gyllenhal, 1827) and Ranunculiphilus faeculentus (Gyllenhal, 1837), in NE Poland are presented. In both species the larvae were found feeding externally on top parts of their host plants, Juncus bufonius L. for the former and Consolida regalis Gray for the latter. These are the first records of larval exophagy in terrestrial members of the subfamilies Bagoinae and Ceutorhynchinae.

Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Bagoinae, Ceutorhynchinae, Bagous lutulosus, Ranunculiphilus faeculentus, biology, exophagous larvae, NE Poland, Biebrza region.

The weevils are first of all known from their rostra, a device for piercing deep holes to lay eggs inside plant tissues, thus allowing the larvae to feed and develop sheltered and surrounded by food supplies. This is the first glance difference from the leaf-beetles and actually the sole morphological character separating the huge phytophagan families Curculionoidea and Chrysomeloidea, decisive about two different evolutionary pathways utilized by these beetles (both highly successful in terms of the achieved biodiversity). Therefore, endophytic larval development initiated by oviposition through the canal prepared with female rostrum is largely prevailing among weevil families, and exceptions are scarce, unless we talk about larval feeding on plant roots in the soil widespread in several huge groups of Curculionidae (incl. Brachycerinae) and even in a part of Brentidae (e.g. Microcerinae). The weevils with fully exophytic larvae, spending whole life exposed on their host plants like chrysomelid larvae or lepidopteran caterpillars, are known in just a few groups, like cyclomine genera Gonipterus, Oxyops, and Listroderes, some aquatic Bagoinae, strictly hygrophilous and aquatic species of ceutorhynchine genera Eubrychius, Pelenomus, and Phytobius, and curculionine tribes Cionini and Hyperini [Scherf 1964] [Marvaldi et al. 2002] [Newman et al. 2006] [Skuhrovec 2008] [Oberprieler 2010]. Nevertheless, this mode of life, undoubtedly a derived one regarding weevils, is expected to be more popular in various groups of Curculionidae. Confirming examples are provided by older larval stages of Dorytomus longimanus (Forster, 1771) (Curculioninae: Ellescini) illustrated by [Kozłowski 2010], on p. 303. Further examples, concerning two other curculionid subfamilies, are presented below.

Field observations were documented on photos using digital camera Nikon Coolpix 4500 for macrophotographs, and Nikon Coolpix S4 for plant views. The photo of larval cocoon was taken under stereoscopic microscope Nikon SMZ1500 and again Nikon Coolpix 4500 digital camera, while for the close-ups of feeding Bagous larvae Leica stereomicroscope M205C with attached digital camera JVC KYF75 was used, all photos being combined using the AutoMontage software of Syncroscopy. Voucher specimens, both the larvae and reared adults, are preserved in my collection at the Museum of Natural History, University of Wrocław (MNHW).

PL: Białowieża Primeval Forest, Stara Białowieża, the clearing adjoining forest compartment no. 282 (UTM: FD84; lat/long: 52.7518/23.7957), 14 VII 1999, 1 larva and 7 teneral adults found on the ground under toad rush Juncus bufonius L.

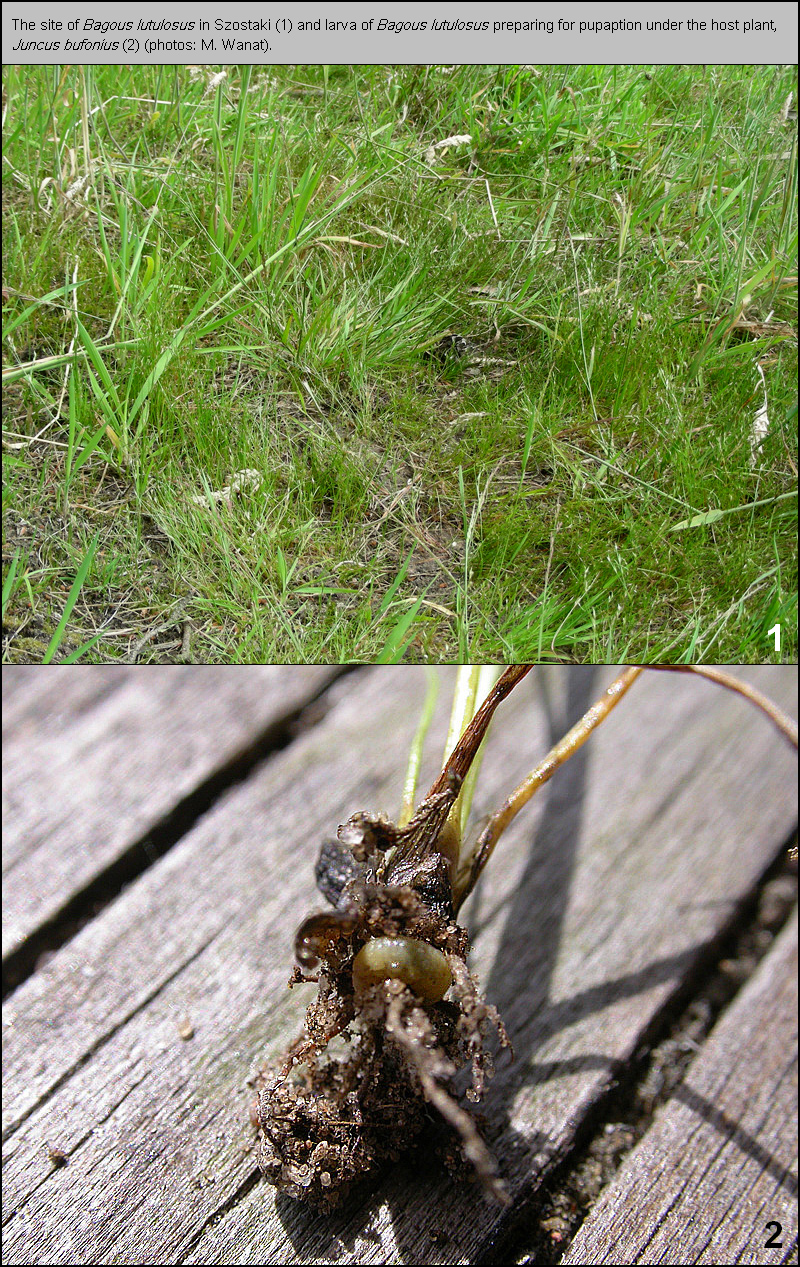

PL: Biebrza National Park (Southern Basin): Szostaki (UTM: EE90; lat/long: 53.2844/22.4606), 7 VIII 1996, 4 adult exs, 16 VI 2010, over 20 larvae observed feeding on J. bufonius in exactly the same place, 6 of them collected and reared to adults in laboratory; Sośnia (Marachy area) (UTM: FE02; lat/long: 53.4744/22.5965), 23 VI 2001, 1 adult; Klimaszewnica, at Klimasówka stream on road to Grządki Małe dune (UTM: FE02; lat/long: 53.44560/22.5218), 23 VI 2001, 1 adult.

PL: Bolimowska Forest: Okop near Skierniewice (UTM: DC46, lat/long: 52.0302/20.2043), 25 - 31 VII 1994, 12 adults, 1 -11 VIII 1994, 5 adults.

PL: Sobibór near Włodawa (UTM: FC80; lat/long: 51.4738/23.6362), fallows W of the village, 8 VI 2001, 1 adult.

The larva from Białowieża while taken to laboratory actively climbed J. bufonius stems and attempted to feed on green tissues. Next day, after addition of some wet soil to the vial, it immediately went inside and remained there until 19 VII (last control). On 22 VII the pupa was detected and preserved in ethanol.

The larvae from Szostaki were taken to laboratory on 16 VI separately in 50 ml plastic vials together with whole plants and small portions of soil surrounding their roots. They were all actively feeding until 22-23 VI, and subsequently entered the soil. The pupal stage was omitted due to lacking controls, and teneral adults were found in all six vials on 3 VII. The larva does not build any cocoon or definite pupal camera [Tab. W67.3].

Central European Bagoinae are predominantly associated with aquatic and semiaquatic habitats and nearly all species develop in water or marsh plants [Dieckmann 1983] [Caldara & O’Brien 1998] [Sprick 2001]. Bagous lutulosus is known among few exceptions regularly found far from water reservoirs [Hoffmann 1954] [Smreczyński 1972], beside B. diglyptus Boheman, 1845, and even xerothermophilous B. aliciae Cmoluch, 1983 [Dieckmann 1983] [Szypuła 1995].

B. lutulosus was already recorded from Juncus bufonius L. [Hoffmann 1954] [Caldara & O’Brien 1998], so the above records only confirm this biological association (Hoffmann’s record from J. obtusifolius Ehrh., currently named J. subnodulosus Schrank, seems dubious). Exophytic larvae have been already known from several species associated with aquatic and typical marsh plants, like B. glabrirostris (Herbst, 1795), B. binodulus (Herbst, 1795) and B. brevis Gyllenhal, 1836, and in the latter two species the larvae are even known to feed on emersed plant parts [Scherf 1964] [Cuppen & Heijerman 1995] [Sprick 2001] [Gosik 2010]. Also in B. frit (Herbst, 1795) the larvae were temporarily found on stem surface of its host plant Menyanthes trifoliata L. [Leiler 1987]. But such mode of larval life, fully exposed on the plant, is something unexpected and unusual among terrestrial bagoine weevils, like B. lutulosus. It was suspected by me since 1999, when a single larva was found crawling on the ground under J. bufonius in the Białowieża Forest, because any part of this tiny plant is sizeable enough for internal feeding for a beetle larva of this size. It has been confirmed in 2010 in Szostaki, that fully grown larvae of B. lutulosus feed externally on toad rush, mainly on florets, where they prepare a round hole through sepals and petals and eat up the contents. Occasionally the larvae gnaw similar holes also in the leaves wrapped around the bract supporting the floret [Tab. W67.1], [Tab. W67.2]. The juvenile larva might be small enough to eventually hide inside the toad rush floret, but later instars were always seen partly exposed from the hole, having too large body to fit in the first prepared cell. Although lacking legs, the larvae are very sticky and easily walk along thin stems and bracts.

The species evidently needs for pupation a permeable, usually more or less sandy soil and avoids regularly flooded places. Both abovementioned sites, where the larvae were found, are exactly of this type, like the other listed localities of this weevil in Poland, where I collected adult beetles. The locality in Szostaki, since 1996 taking just a few square meters [Tab. W67.3], is situated at the very base of a sandy slope of Biebrza river forested with pines, and in 2010, when the level of spring river overflow was very high, it still remained out of flood range. Analogously, the localities in Sośnia and Klimaszewnica are on elevated areas, while the weevil had never been collected by me from several muddy roads in the Biebrza valley, mostly along dikes, where the host plant was very common and locally formed dense carpets. The plant is damp-dependent and fragile to seasonal droughts, so it may appear ephemerally, like the weevil. In the subsequent year (2000) in Białowieża, characterised with a very dry summer, the plant was detected in just several dwarf specimens, and no weevil was observed on the forest clearing. Considering relatively short development and disparate dates of collecting teneral adults it seems likely, that at least in some years, depending on weather circumstances, two generations of the weevil may well complete development in one season.

Based on adult morphology [Caldara & O’Brien 1998] placed B. lutulosus near B. brevis Gyllenhal, 1836, which lives monophagously on Ranunculus flammula L. from the dicot family Ranunculaceae, but apparently has quite similar biology. In the Netherlands its larvae were found feeding exposed on leaves and stems of the host plant, pupation is almost certainly in the soil, and no pupal chambers were observed [Cuppen & Heijerman 1995].

Biebrza National Park (buffer zone of Southern Basin), Mocarze (UTM: EE90; lat/long: 53.2909/22.4585), small gravel-pit in agrocoenose, 26 V 2003, 1 larva from Consolida regalis Gray.

A brightly yellow larva was found exposed on the top of plant, feeding on green tissues of the top bud. While taken to laboratory it soon pupated in the soil, first preparing a cocoon of sticked sand grains [Tab. W67.4]. The pupa was removed from the cocoon and preserved in ethanol.

Ceutorhynchinae are known as stem or root neck borers, seed eaters, or leaf miners, and only in several Phytobiini (genera Phytobius, Eubrychius, Pelenomus) the larvae feed on leaves and pupate in external cocoons [Scherf 1964] [Dieckmann 1972]. The larva of R. faeculentus was found well exposed and clearly seen on a green plant due to its yellow colour. Probably it can partly hide within the loose top leaf bud, but the plant does not offer an opportunity for full endophagy in its upper vegetative parts for the mature larva of the weevil. It appears the first observed case of exophagy in this weevil genus, and the whole tribe Ceutorhynchini.

Since only one larva was found in the above circumstances, and it pupated soon after, that it was caught during accidental translocation can not be definitely excluded. However, the feeding by the larva was clearly observed, the larva had brightly colored body when alive, which is not typical for endophages, and no galls were detected on the examined plant specimen. In Ranunculiphilus lycoctoni (Hustache, 1917) living on another Ranunculaceae, Aconitum lycoctonum L. and A. napellus L., the biology is quite different. Its larve are endophagous and form stem galls below the inflorescence, and pupation takes place in the gall, not in the soil [Dieckmann 1969].

I thank Krzysztof Frąckiel and Rafał Ruta for the assistance in searching for the larvae of Bagous lutulosus, KF also for one tasting session of a good representation of his fantastic self-made liqueurs. I am also grateful to the heads of the Biebrza National Park for a long term permission and support of my weevil studies there. Rafał Gosik is thanked for critical review of this manuscript.